In September 2025, as Wisedāna Foundation we had the privilege of meeting Geshe Tenzin Tenphel at the Lama Tzong Khapa Institute (ILTK) in Pomaia, one of the most important Buddhist centers in Italy and Europe. Founded in 1977 by Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, ILTK is affiliated with the international network Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) and today stands as a key reference point for the study and practice of Tibetan Buddhism, having hosted His Holiness the Dalai Lama on several occasions.

During our meeting with Geshe Tenzin Tenphel, we received a precious teaching on generosity: words simple in form yet carrying a depth that still resonates with us.

For those unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhist terminology, “Geshe” is an academic title equivalent, in commitment and intellectual depth, to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy. It is a degree reserved for great scholars of the Gelug school—the same tradition as the Dalai Lama—reached after decades of study, debate, and contemplative practice.

Before meeting Geshe Tenzin Tenphel, we learned more about his story. Born in Tibet, like many monks and nuns of his generation he was forced to leave the country following the Chinese occupation, becoming part of the Tibetan diaspora. In India, he began his training at Sera Je Monastery, where he completed his foundational studies. He then attained the title of Geshe Lharampa, which requires at least twenty-three years of rigorous study, and later continued his training at the Gyuto Tantric College. Since 1998 he has lived in Italy as a resident teacher at ILTK. He is widely appreciated for his extraordinary ability to convey profound concepts with simplicity and a touch of humor.

The pāramitās

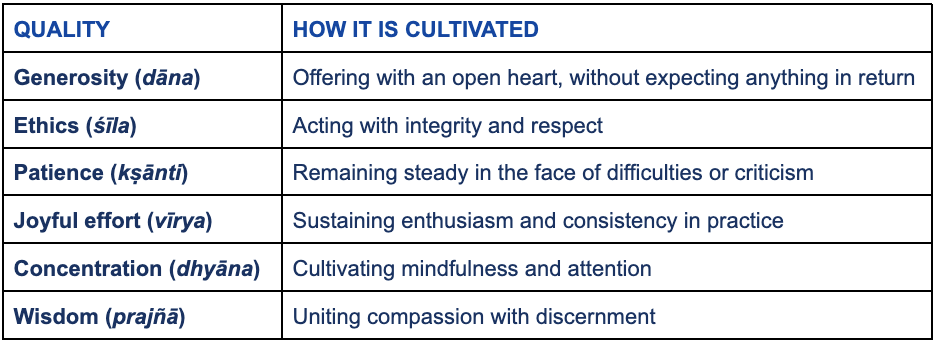

During his teaching, Geshe Tenzin Tenphel reminded us that generosity is not only an external act, but above all an inner quality to be cultivated. In Tibetan Buddhism, this virtue is known by the Sanskrit term dāna—yes, the very same “dāna” at the heart of our name and mission as a Foundation—and it is considered the first of the pāramitās, the “perfections” that guide the spiritual path.

The pāramitās are qualities that every practitioner is encouraged to develop in order to reduce selfishness, loosen attachment, and move toward freedom from suffering. They are not abstract ideals, but very concrete virtues with direct applications in daily life and in our relationships with others.

In the different Buddhist traditions, there are varying lists of pāramitās. In the Theravāda school, widespread especially in Southeast Asia, there are ten perfections, while in the Mahāyāna tradition there are six. In both, however, generosity comes first, often described as the gateway to all the other virtues.

The six pāramitās in Tibetan Buddhism

According to Geshe Tenzin Tenphel’s teaching, an act of giving can be performed in a superficial way, but genuine generosity only blossoms when it is supported by the other qualities, which preserve its purity and its transformative power.

Ethics reminds us that giving alone is not enough: what truly matters is the way we live. If our conduct is inconsistent, the act of generosity loses part of its strength. Patience is essential because a gift does not always produce the outcome we hope for. Sometimes we receive criticism, complaints, even accusations, and without patience our deeper motivation can easily falter. Joyful effort makes the practice of giving sustainable over time: not a duty, but an act carried out with enthusiasm and lightness. Concentration helps us stay present: when we give, we are fully aware of the act we are performing and of the good intention behind it. Finally, wisdom guides us in discerning how, when and to whom we give, ensuring that our resources are not wasted or used in ways that fail to bring genuine benefit.

When these qualities accompany generosity, the gift becomes more than a simple exchange: it turns into a practice capable of easing suffering and strengthening the bonds of interdependence that connect us all.

The three inseparable elements of generosity

When speaking about generosity, Geshe highlighted a fact that seems almost obvious but is often forgotten: a generous act is never isolated. Every gift rests on three inseparable elements—the giver, the gift itself and the receiver. None of these can exist without the other two.

The giver is the one who cultivates the intention to offer, free from miserliness and guided by a sincere wish to bring benefit. The gift can take many forms—money, time, food, knowledge, care—and it is not measured by its quantity but by the quality of the intention that accompanies it. The receiver, finally, is never a passive figure: it is thanks to those who receive that the giver has the opportunity to practice generosity. Without this relationship, the gift could not come into being.

This simple yet powerful reflection leads us to recognize the interdependence that binds the three elements together. The giver stands on the same level as the receiver, bound together by the dynamic of the gift that benefits both. And since life is always changing, if today we are the ones offering something to others, tomorrow—in different circumstances—we may find ourselves in the position of receiving.

Maintaining the purity of intention

Practicing generosity also means accepting that not everything will unfold as we imagine. Those who receive our gift may respond in different ways: with gratitude, with indifference, or even with criticism. If we allow these reactions to shape our motivation, generosity weakens and risks turning into frustration or aversion.

For this reason, the teacher reminded us of the importance of cultivating a stable mind, one that is not shaken by the ups and downs of circumstances. Genuine generosity does not seek recognition or reward; it arises from an authentic wish to bring benefit. Giving is not a way to strengthen one’s ego, but to open a space of connection and compassion.

Living generosity in this way means developing equanimity: seeing in others not someone “below us” to whom we grant something, but a fellow human being, who today receives and tomorrow may be in the position to give. It is this balanced outlook that transforms giving from a simple act into an inner practice capable of easing suffering.

Gratitude for the teaching

When the master concluded his teaching and left the hall, a dense silence remained in our minds and hearts, filled with the echo of his words. It was an opportunity to deepen a theme that accompanies us every day: generosity as a practice that transforms both the giver and the receiver.

It was a privilege to do so guided by the clear gaze and genuine laughter of Geshe Tenzin Tenphel, who with disarming simplicity reminded us that authentic generosity is free from ego, sustained by wisdom and rooted in equanimity. A generosity that recognizes the interdependence between giver and receiver, and that does not lose heart in the face of difficulties or unexpected reactions.

We are grateful to Geshe Tenzin Tenphel and to the Lama Tzong Khapa Institute for their welcome and the opportunity for dialogue. And we are grateful to you, the reader: because every reflection shared is already a seed of transformation.

Written and edited by Marta Turchetta

Photos by Pexels