In our previous article on the topic of conflict, we explored with Martina Righetti, a conflict coach, mediator and founder of Parliamoci di Brutto, how different approaches to conflict can turn it into an opportunity for growth rather than a cause for breakdown. In this second interview with Martina, we delve deeper into the dynamics of conflict that concern us more directly.

Why do we often feel fear and guilt during conflicts? What reactions do our mind and body experience in these situations, and how can we manage them? Is it possible that even in a well-managed conflict, a common solution is not found? Thanks to years of experience, first as a corporate lawyer and then as a mediation professional, Martina helps us answer these questions, focusing on the psychological, physiological and relational dynamics that are present in every conflict.

Many people do not perceive conflict as a positive opportunity, but rather fear it. Why?

Part of our cultural and educational models teach us to avoid confrontation, to be “good” and agreeable, to flatter and appease, and to maintain control.

Conflict, by definition, makes us lose this control, not because we cannot manage our emotions (we absolutely can, if we learn how), but because, in order to reach agreements, we need to be open to the possibility that the other person has something valuable to ask. In other words, we need to be open to being disagreed with, contradicted, to feeling lost, frustrated, uncertain. In conflict, we are called to question our initial positions and to find creative ways to also embrace the needs of the other person. We know that we might fail, that we may not reach an agreement right away, or at all. This uncertainty scares us, even though it is far more real than the illusion of control we think we need.

How do we usually react to this fear, and how could we manage it better?

It’s a fear that should be recognized, embraced and accepted. Only by doing so—by stopping ourselves from judging and rejecting it—can we begin to rewrite our narrative of what happens during a conflict in an evolutionary way. As I often say, we should learn to shift our view of conflict:

from melodrama → self-victimizing and regressive

to tragedy → mindful and transformative

With this metaphor, I mean to say that conflict management begins with how we tell the story to ourselves: if we isolate ourselves in the role of victim, we will feel fear, anger and frustration, whereas if we open ourselves to uncertainty and the needs of others, we will feel united with them in the shared effort to find a truly satisfying solution for all parties involved.

What role does guilt play in conflicts?

Guilt is a good ally of avoidance: it leads us to withhold what we need because we fear the other person’s reaction, as we don’t want to cause them pain. In practice, if we know we might react explosively during an argument, this makes us feel guilty. Instead of addressing the issue calmly, we close ourselves off and completely avoid the conflict. In this regard, it’s important to remember that avoiding a conflict doesn’t mean resolving it but burying it, making it harder to identify and manage.

On the other hand, a sense of responsibility is an excellent ally in taking an effective and mindful approach to conflict: it encourages us to take control of our choices, to understand what we truly want, and to decide how to express it outwardly in a non-blaming way. We take responsibility for our emotions and return responsibility for the other person’s emotions to them, all while remaining compassionate, welcoming and non-judgmental.

What happens to the body when we enter into conflict?

In my years of work as a conflict coach and mediator, I have witnessed many kinds of reactions, which also differed at the somatic level. The most common expressions include tension in the abdominal area, the sensation of the so-called “lump in the throat,” and persistent anxiety or agitation caused by circular thoughts related to the ongoing conflict. It is common for someone experiencing a poorly-managed conflict to constantly think about all the possible solutions to end it as soon as possible, even though many of these solutions are unrealistic attempts or unilateral approaches, and therefore not real solutions.

Are there practices to interrupt an internal escalation when we feel the tension rising?

During an emotionally intense argument, I love inviting people to practice presence. It’s a very simple, reproducible practice that can be done anywhere and is surprisingly effective. Let me briefly explain it.

You need to ask the other person for a break from the conflict: “I need us to stop, I know you’d like to continue, but I need a few minutes of pause”. Then, you move to another room or a safe corner of the same room, and touch something colder than your body (a door handle, the wall, a glass vase). While keeping contact with the object, you close your eyes and, while breathing, focus on the tactile sensation of that moment. Through your hands, you release the heat of anger, frustration and other exhausting emotions. You can open your eyes when the sensation of cold becomes more intense than the heat caused by agitation.

Is it possible to have a conflict with ourselves (the so-called “inner conflict”)?

It is certainly possible. As a matter of fact, within us there is always an active and sometimes conflicting dialogue that we can learn to recognize and rewrite in a more harmonious way (this is part of the work I do on inner narrative). “Purists” of conflict management prefer to see conflict as a phenomenon that only arises in the presence of a relationship between two or more people, but the dynamics that occur when we experience conflict with ourselves are not very different from the forces that govern interpersonal conflicts.

What should we do when we’re not an active part of the conflict but are assisting in it?

Sometimes, we are not directly involved in a conflict, but we find ourselves mediating or facilitating the dialogue between the parties. In these cases, we can assist in a non-judgmental way and with a coaching style, helping the conflicting parties develop the right mindset to approach the situation mindfully. In such cases, it is helpful to have specific skills, but the fundamentals are always the same: a non-judgmental attitude, emotional acceptance and active listening. The ability to ask Socratic and open-ended questions also comes into play—questions that do not suggest an interpretation but invite real reflection, going beyond the simple “yes” or “no” answer.

What should we do when a conflict doesn’t seem to lead to an agreement?

As I often advise those who work with me, it’s important to remember that a single argument or negotiation does not represent the entire scope of the conflict. The conflict is indeed broader and includes various “rounds”. Let me explain with an example: it can happen that there is an initial explosive conversation, followed by a moment of individual reflection, which leads to a clarifying discussion when emotions decrease in intensity, followed by one or more exchanges of proposals and counterproposals. Episodes like these form the different rounds of the conflict, through which it is possible to reach a final agreement.

It’s also important to emphasize that the lack of an agreement is not symptomatic of failure in the relationship. Sometimes, the conflict does not lead to a shared solution but to the choice of different solutions for each of the parties involved. It can happen that a certain issue belongs to one’s personal sphere of choice, and therefore, one is not willing to make it a subject of negotiation. In this regard, something I often tell the people I work with during mediations is: “Disagreement is an option. But it’s also a new opportunity!”

In cases of disagreement, it is helpful to reflect on how a choice is communicated, embracing the reactions it generates and working on our ability to manage those reactions. The Nonviolent Communication approach by psychologist Marshall B. Rosenberg is very useful in this sense because it delves into the importance of empathetic communication in conflict situations.

Is there a winner and a loser in conflicts?

If during a conflict we feel that the “rules of the game” assign roles of winners and losers, we are likely dealing with an antagonistic-competitive conflict. This is the type of conflict in which at least one party imposes its will on the others, through forms of control, blackmail or manipulation, whether consciously or unconsciously.

In contrast, in an effective conflict approach based on trust, the possibility is created for all parties involved to bring out their interests and emotions. In this way, and this way only, are the necessary conditions in place to negotiate truly satisfying and lasting solutions.

In conclusion, conflict, which is a natural and therefore inevitable way of relating to others, can be managed in many ways. Different approaches to conflict make the difference between a constructive and a destructive outcome to the conflicting situation. To transform conflicts from causes of suffering and isolation into opportunities for growth and connection, each of us can cultivate virtuous practices and attitudes in this regard.

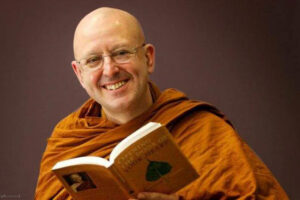

A key element is self-awareness: being aware of our emotions—yes, even and especially the negative ones—our physical reactions, our role in the conflict and the words we use to communicate. Only by cultivating awareness of ourselves can we begin to manage conflict with the outside world effectively and positively. A second crucial factor is our openness to uncertainty: if we learn to embrace unexpected situations and positions different from our own as entirely possible events, we can finally stop trying to control the uncontrollable and start working toward a creative solution. Living with greater awareness and embracing uncertainty are practices also encouraged by Buddhism, as reminded by the British-born Buddhist monk Ajahn Brahmavamso Mahathera:

«Letting go of the ‘controller,’ staying more with this moment and remaining open to the uncertainty of the future frees us from the prison of fear. It allows us to respond to life’s challenges with our innate wisdom and to emerge unscathed from many complicated situations.»

Ajahn Brahm, Opening the Door of Your Heart, Hachette Australia Pty Ltd (2004)

Written by Marta Turchetta and Martina Righetti

Edited by Marta Turchetta

Photos by Pexels